Pelvic Pain in Athletes

Pelvic pain in athletes involves a wide spectrum of differential diagnoses. Is it orthopedic? (A labral tear? A pelvic girdle issue?) Or perhaps myofascial? (Pelvic floor? Adductors?) Neurological? (Pudendal? Obturator?) Biopsychosocial? Dermatological? Vascular? The possibilities are endless…

Today’s therapist working with dysfunctions in and around the pelvis needs a solid grounding in the many different body systems that pass through the crossroads of the body – paying respect to not only the mechanical effects and issues associated with the biomedical systems that traverse the pelvis (neuro, musculo-skeletal, digestive, or vascular, to name a few), but also the biopsychosocial layers that can influence pelvic pain.

Biopsychosocial causes

To use an example from the Wise–Anderson team in A Headache in The Pelvis,1 think of how a dog behaves when he is happy – a lot of tail wagging and freedom of movement, right? But when a dog is scared or in pain, that tail gets firmly tucked between its legs.

Now, imagine you are a collegiate athlete, dependent on a scholarship for your continuing education and you hear the dreaded diagnosis of ‘groin strain’ or ‘labral tear’ or ‘pudendal neuralgia.’ That stress has the potential to be stored in the emotionally responsive muscles of the pelvic floor and other lumbopelvic allies, such as the psoas and diaphragm. This adds another layer of mystery and intrigue on the path to finding the correct/causative issue that started the cascade of pain and dysfunction.

Lumbopelvic canister

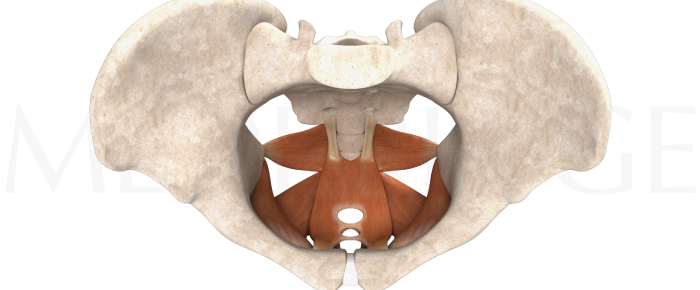

Many sports medicine therapists are intimidated by a possible pelvic pain diagnosis. We have all acknowledged that the pelvic floor is part of the lumbopelvic canister system, described by research that emerged in the late 1990’s from luminaries such as Paul Hodges.2 Further research has possibly negated the role of specific ‘core stability’ training vs. generalized exercise training when it comes to lumbo-pelvic pain. The current clinical practice leans more towards functional integration of the ‘canister muscles,’ particularly the diaphragm and pelvic floor. This approach depends on establishing fully functional ranges of motion and coordination more than previous models of ‘bracing’ in relatively static positions – which is not an efficient or effective rehab strategy.

Pudendal nerve

Diagnoses such as Pudendal Neuralgia or Pudendal Entrapment can intimidate the orthopedic or sports medicine therapist. However, as Dornan writes in his 2012 paper A musculoskeletal approach for patients with pudendal neuralgia: a cohort study, ‘…Selected patients with pudendal neuralgia and low back pain responded favourably to education, postural advice, and mobilisation and exercises directed to the lumbopelvic region.’3

The pudendal nerve supplies much of the sensory, motor, and autonomic requirements of the pelvis and has a very circuitous route through the pelvis. It originates from S2,S3, and S4, winding under, over, and through such structures as the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments, piriformis, obturator internus, and the pelvic floor muscles themselves.

In Part two of this post, we will look at how a thorough neuro-musculo-skeletal assessment and treatment approach can demystify this mysterious diagnosis (once the appropriate urological/gynecological/medical testing has been cleared). It is our responsibility to provide answers to this unfortunately common (and commonly misdiagnosed) phenomenon, particularly with our athletic population.

- Wise & Anderson ‘A Headache in The Pelvis’ National Center for Pelvic Pain; 6 Revised edition (March 1, 2012)

- Hodges & Richardson. ‘Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis’. Spine 1996; 21(22): 2640–2650.

- Dornan, P & Coppieters, M ‘A musculoskeletal approach for patients with pudendal neuralgia: a cohort study’ BJUI 2012 DOI: 10.1002/BJUIw-2012-054-web