Life After the Ventilator: Swallowing Following Extubation

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in New York City, patients flooded into ERs with such severe respiratory distress that many required mechanical ventilation to assist with their breathing.

Because of the well-publicized shortage of life-saving ventilators, the media often covered stories in which patients had been fortunate enough to gain access to ventilators and were then removed from the machines upon recovery.

These patients’ stories presumably finished at the time of extubation. Yet for many, a long, difficult journey was only beginning.

Intubation-Associated Challenges

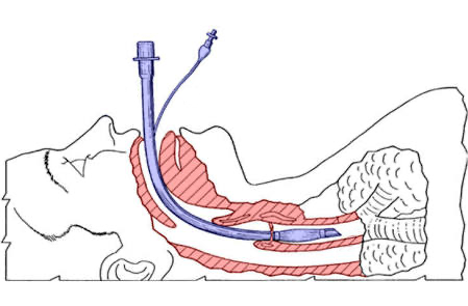

Connecting the ventilator to the patient requires intubation, which is done by passing a tube through the mouth, down through the larynx and to the trachea.

The upper airway contains the vocal folds and other groups of muscles involved in changing the tone of our voice, allowing for volume control and also assisting with protection of the airway during swallowing—that moment when we swallow and must stop breathing to ensure the food and liquid go into the esophagus, not the airway. With an endotracheal tube (ETT) in place, these muscles are now immobile, in addition to those in the oral cavity. With disuse of muscles comes atrophy, often in the form of weakness.

Our speech-language team has been answering consults in acute care for patients with a positive COVID-19 diagnosis since the onset of the pandemic. Many of these patients have recently been extubated or had the ETT removed, and many consults have been for patients with respiratory deficits and decompensation due to COVID-19. An average of 30 percent of patients admitted to a hospital in Brooklyn were intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation. This rate is in line with the numbers reported at hospitals throughout New York City. Once extubated, patients need varying amounts of oxygen support to breathe on their own. The next question becomes: Can the patient swallow safely, limiting the risk of aspiration?

Swallowing Examinations in the Age of COVID-19

The Barrique SLP team, who are also clinical instructors and alumni of New York Medical College (NYMC), have been conducting clinical swallowing examinations at bedside to determine how safe it is for the patient to eat by mouth. Due to the high risk for viral spread in the oral and pharyngeal cavities, many institutions have stopped scheduling several of the instrumental exams that speech-language pathologists often rely on to further evaluate the swallowing mechanism. These include endoscopic exams and radiologic exams (videofluoroscopy or modified barium swallow study).

This means that speech-language pathologists have had to make clinical decisions based on limited diagnostic information. In addition, recovery patterns for patients with COVID-19 vary and remain mostly unknown. Some symptoms improve gradually, others suddenly, and still others take even longer than usual to subside.

Some of these factors have changed as the pandemic has been curtailed in the Northeast, but much is still to be learned about changes that have taken place in our clinical practices.

Restoring Swallowing

The goal is to get patients to start tolerating some food or liquid by mouth as soon as possible, even if not enough for a full meal. This allows the muscles to start working again and restores the coordination of swallowing and breathing to regain function, safety, and efficiency.

For patients who remain sufficiently alert, some exercises to help strengthen and/or coordinate muscles of the mouth, throat, and upper airway may be of benefit. These exercises include:

- Effortful pitch glides that target the pharyngeal muscles

- Cough strengthening exercises

- Repetitive “ee” sounds that targeting the base of the tongue

- Respiratory resistance exercises, such as expiratory muscle strength training

While all exercise programs are individually tailored, the common goal is the same: To allow food and liquids to travel from the mouth to the esophagus efficiently and safely.

So far, we’ve been able to return patients who successfully remain off the ventilator to full diets by mouth with varying degrees of success. Some patients with COVID-19 are so debilitated or decompensated that they require additional nasogastric or gastric tube feeding support. This may be temporary or more long-term, depending on each patient’s needs. Our team works hard to prevent the need for tube feeding, but when it’s necessary, we provide recommendations as to what a patient may still manage by mouth, even if they are on tube feedings for support.

The ability to swallow safely impacts overall nutrition, which in turn impacts the patient’s progress toward returning to pre-COVID-19 functional status. This requires great medical care, as well as good rehabilitation, working closely with our physical therapy, occupational therapy, and respiratory therapy colleagues. Along with the medical team, we are all working toward the common goal of ensuring the best patient outcomes.