Biomechanical Demands of Ballroom Dance

Are All Dancers Created Equal?

The majority of rehabilitation clinicians recognize the uniqueness of the athletic prerequisites of their patient’s sport. For example, you can probably identify a difference in physical requirements between a tennis player and a table tennis player. While it might seem obvious to anyone that both sports require fast reaction time, thoracic mobility, and stability, you also likely recognize that the shoulder and lower extremity range of movement will be significantly different. Considering these factors, you would then create an individualized rehabilitation protocol for both of these different types of athletes.

But what if the patient is a dancer instead? Are all dancers created equal? Do you automatically consider working on core stability and hip mobility?

With a better understanding of the intricate movement patterns and vital biomechanical requirements, you’ll be able to provide better injury prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation to ballroom dancers.

Competitive Ballroom Dance

Competitive ballroom dance1 is a rapidly expanding industry, and with its growth, physical therapists and athletic trainers are seeing more professional and amateur dancers in their clinics.

Ballroom dance comprises two major categories: Standard and Latin.

Standard dances include:

- Waltz

- Foxtrot

- Tango

- Viennese waltz

- Quick-step

Latin dances include:

- Cha-cha-cha

- Rumba

- Samba

- Paso doble

- Jive

The biomechanical demands of Standard and Latin dances are remarkably different, requiring individual discussions.

Standard Style Biomechanical Demands

Miletic, et al.,2 found that the most common male Standard dancers’ injury sites were in the upper back, while female Standard dancers tended to experience injuries in their upper back and neck.

The “frame” is a characteristic feature of the Standard dances. It must be sustained by both partners for the duration of the entire dance, usually one-and-a-half to two minutes, and repeated five times since all five dances are performed back to back. The frame is formed by both partners, the leader and the follower. The leader’s role is to navigate the couple across the dance floor, while the follower’s role is to follow the leader while sustaining a beautiful and elegant posture.

The “frame” is a characteristic feature of the Standard dances. It must be sustained by both partners for the duration of the entire dance, usually one-and-a-half to two minutes, and repeated five times since all five dances are performed back to back. The frame is formed by both partners, the leader and the follower. The leader’s role is to navigate the couple across the dance floor, while the follower’s role is to follow the leader while sustaining a beautiful and elegant posture.

Several biomechanical requirements are necessary on the parts of both the leader and follower to correctly create the frame:

Requirements for the leader:

- Neutral spine posture

- Shoulder girdle abduction 90°

- Right shoulder 10° internal rotation

- Left shoulder 30° external rotation

When assessing or treating a ballroom dance leader, you’ll need to immediately recognize the difference between the right and left upper extremity requirements. This posture produces a high demand of the shoulder girdle musculature such as the deltoid, rotator cuff, and scapular stabilizers. These muscles have to be trained isometrically at the ranges stated above. You must examine the dancer’s ability to stabilize at the shoulder girdle and thoracolumbar region.

Requirements for the follower:

Requirements for the follower:

- The shoulder girdle must be the mirror image position of the leader.

- Lumbar and thoracic spine extension

- Cervical spine rotation to 70°

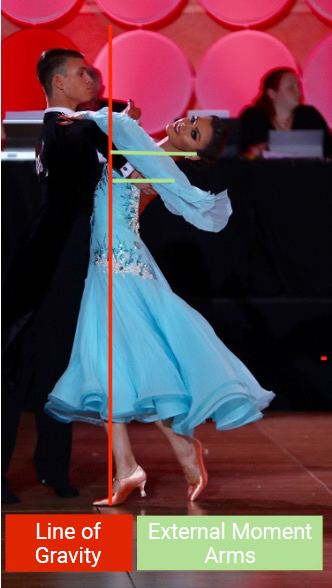

Here, you must consider the kinematics and the kinetics of this posture. Kinematically, you must examine the thorax’s ability to extend and the upper and lower cervical spine’s ability to rotate. Kinetically, you need to be aware of increased external torque.

The follower’s center of mass is shifted posterior, which increases the external torque pulling the upper thorax into extension. The external torque’s posterior displacement creates greater compression forces on the vertebrae’s posterior elements, such as Z-joints and the posterior disc. The anterior longitudinal ligament and the anterior disc are now subject to increased tension forces. The sustained neck rotation will further exaggerate the compression unilaterally.

These physiological demands may explain the frequency of upper thoracic pain and injury in Standard dancers.

Latin Style Biomechanical Demands

Latin dancers have radically different biomechanical requirements than Standard dancers.3 In Latin dance, both males and females follow a similar step pattern and often mirror one another’s movements.1

McCabe, et al.,4 found that most Latin dancers presented with injuries in the lower extremity, the trunk, and spine. In Latin dance, the steps are composed of fundamental movement patterns, which typically involve rotary-dissociations through the lumbar spine and the pelvic girdle.

The rotary dissociation described above is created by torsion of the bilateral sacroiliac joints, lumbar spine rotation, hip rotation, and thoracic spine rotation. Studies have shown high activation of external, internal oblique, and gluteal musculature during these specific movements.5

The rotary dissociation described above is created by torsion of the bilateral sacroiliac joints, lumbar spine rotation, hip rotation, and thoracic spine rotation. Studies have shown high activation of external, internal oblique, and gluteal musculature during these specific movements.5

As we know, lumbar facet joints are positioned in the sagittal plane; therefore, these joints limit any rotary motion. You should be aware of excessive rotational requirements and make sure there is sufficient range available through the thorax and hip joint regions.

Give careful consideration to examination of the sacroiliac joint complex. Latin dancers tend to favor the use of one lower extremity, especially in performance of basic movement patterns,1 creating torsional forces through the sacroiliac joint. Examining strength and range-of-motion discrepancies between the right and left sides will guide you to a better patho-mechanical diagnosis hypothesis. The biomechanical intricacies of Latin dance confirm the reports of spine and trunk pain, and you should examine at least one or two levels above and below the pain region.

Ballroom dancers are a fast-growing athletic population, deserving of AT, PT, and OT recognition of this sport’s individuality. As with any sport, a clinician’s responsibility is to investigate the complex requirements and generate sport-related biomechanical hypotheses when treating a ballroom dancer. With a targeted individual approach, you will be able to establish a good rapport, develop a specific care plan, and return the dancer to a pain-free competitive state.

- Laird, W. & Laird, J. (2003). The Laird Technique of Latin Dancing. International Dance Publications: Brighton, England.

- Miletic, A., Kostic, R., Bozanic, A., & Miletic, D. (2009). Pain status monitoring in adolescent dancers. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 24(3), 119–123.

- McCabe, T. R., Wyon, M., Ambegaonkar, J. P., & Redding, E. (2013). A bibliographic review of medicine and science research in dancesport. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 28(2), 70–9.

- McCabe, T. R., Ambegaonkar, J. P., Redding, E., & Wyon, M. (2014). Fit to dance survey: A comparison with dancesport injuries. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 29(2), 102-10.

- Liébana, E., Herraiz, E. B., Monleón, C., & Pablos, C. (2017). Muscular activation in rumba bolero in elite dancers of dancesport. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 12(3 proc), 807–812.