Six Actionable Ways to Be a Better LGBTQIA2S+ Ally

LGBTQIA2S+. Does it seem like that acronym is ever-growing? That’s because it is!

As our society evolves, more people are feeling safe and comfortable to live as their authentic selves, and every day there is more evidence to support that.

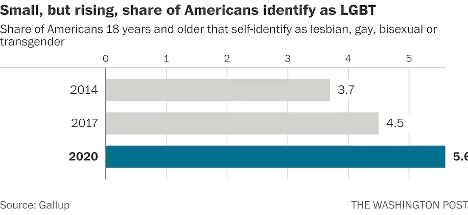

According to Gallup polls, the percentage of people in the U.S. that identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender has increased to 5.6 percent.3 That is three times the entire population of Colorado! These numbers are even higher amongst younger generations—up to 20 percent in Gen Z and millennials by some estimates. In 2019, nearly 80 percent of surveyed Americans state that they personally know someone who identifies as LGBTQIA2S+ or queer.2 And while the word “queer” has a nasty history as a derogatory slur, it is increasingly used by folks in the LGBTQIA2S+ community to describe those who does not identify as cisgender or heterosexual.

What Is the Importance of Sexual Orientation or Gender Identity in Healthcare?

Recent years have provided a groundswell of awareness building around this community—from representation in entertainment, discussion about participation in athletics, and changes occurring at the legislative level. However, one area of society in which awareness is still lacking is in modern-day medicine, so let’s explore the significance of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) as it pertains to healthcare.

As a medical professional, you may wonder “Can’t I simply treat all people the same?” While this idea may be filled with good intentions, the unfortunate reality is that we do not yet have access to this utopian future. There are real, measurable differences in the health of all marginalized communities, including gender and sexual minorities (GSM).

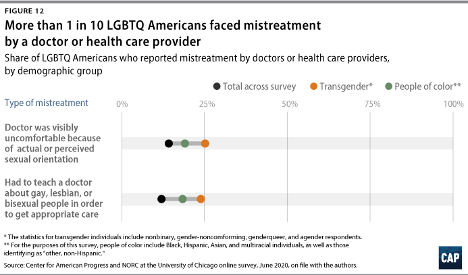

In 2020, 1 in 10 LGBTQIA2S+ Americans faced some form of mistreatment from a healthcare professional.1 These negative experiences strongly correlate with postponing or altogether avoiding medical care in the future, further contributing to the collective LGBTQIA2S+ fear of discrimination. The statistics are even worse when specifically looking at queer and trans people of color.

What Can You Do as a Healthcare Provider?

While the system and the education that trains our clinicians could benefit from a renovation, here are six actionable steps you can take now to facilitate a safer space for your LGBTQIA2S+ patients:

1. Recognize your own potential to cause harm.

As healthcare professionals, we have some degree of inherent privilege. With this privilege comes the capacity to inflict harm, intentional or not. While intentions matter, they do not supersede the impact your words or actions have on another. Assumptions matter, too. While assumption making is common and normal—an evolutionarily advantageous adaptation of the brain—they are not facts, and they are not harmless. Erroneous assumptions about a person’s gender or sexual identity by a medical professional can lead to behaviors that cause discomfort in and discrimination towards LGBTQIA2S+ patients and clients, even if inadvertently.

By recognizing the power differential that exists in the patient/provider relationship and the implications that come with it, we are likely to be more aware of our words and actions when they come up, and more willing to address them when they do. And by taking a position of genuine care and curiosity rather than assumption, we can affirm the relationship between the person whom we are helping and their body.

2. Update your language.

Always use the correct pronouns and name of the person with whom you are working. One easy way to do this is simply by mirroring the language they use when describing themself. However, if you are meeting someone for the first time, you may unintentionally use language that is not in line with your patient or client’s identity. For example, you may use someone’s dead name (the name assigned to them at birth) which may still be listed on their legal and medical documentation.

You can preempt this kind of unintentional harm by including areas for clarification on intake paperwork. This will allow you the opportunity to affirm the pronouns of the person in your care upon your first interaction. While pronoun affirmation may seem like a small action, it has shown to be effective in reducing suicidal ideation and depression.4 Another way to update your language for greater inclusivity is by using the term “spouse” or “partner” when inquiring if a patient has someone at home that can help with their activities of daily living or rehabilitation. Additionally, when referring to pregnancy, birthing, and postpartum care, practice saying “pregnant person” or “birthing parent” rather than “pregnant woman” or “mother.”

3. Speak up….even if the LGBTQIA2S+ person or target of the harm isn’t present.

Shaming someone’s behavior is unlikely to result in positive change or self-reflection. Instead, we can follow the steps of stopping, educating, and being proactive to foster learning in our colleagues. This kind of dialogue offers the opportunity for the individual to participate in the discussion by learning about their behavior, rather than feeling pushed out of the conversation which could limit their chance to grow.

- First, STOP the discussion or action taking place by intervening with “Those words can be hurtful.”

- Next, EDUCATE in lieu of asserting judgment. Proceed from a lens of curiosity. Asking the person “Do you know what those words mean?” or genuinely inquiring about their intention and understanding. Doing this will facilitate conversation and enhance one’s knowledge of their damaging actions, reducing the chance that they will repeat the harmful behavior.

- Finally, BE PROACTIVE by following up with resources for further learning such as GLMA, WPATH, or The Fenway Institute.

It is important to note the significance of taking this action even if the LGBTQIA2S+ person was not present for the encounter. This breaks the notion that harmful language is acceptable so long as the subject of the harm is not privy to it. If the LGBTQIA2S+ person is present for the encounter, it is best to first pull them aside to check in with them, make sure they are alright, and ask if they want your help. Some folks prefer to avoid drawing attention to themselves. It is also a skill of allyship to know when not to talk.

4. Be receptive to feedback.

When a LGBTQIA2S+ person, or a person from any marginalized group for that matter, corrects your language or behavior, practice saying “thank you” rather than “sorry” and avoid explaining yourself. It is a privilege to learn about oppression rather than to experience it for yourself. When someone corrects you, not only are they bravely honoring their authentic identities, but they are doing emotional labor on your behalf, and in the age of freely available information, it is never the responsibility of marginalized folks to educate others for free. These interactions are opportunities for personal growth—don’t let them pass you by!

5. Suggest practical changes to make the workplace more inclusive.

Does your workplace have gender-neutral bathrooms? Many LGBTQIA2S+, queer, and trans people avoid using public restrooms to avoid harassment and violence. Such aggressions can have very tangible consequences to their physical health, such as pelvic floor dysfunction. If there aren’t any inclusive restrooms in your workplace, make a suggestion to change that.

How inclusive are the brochures in your waiting room? Do the patient education materials that you provide to a patient after evaluation use language and imagery that include the LGBTQIA2S+ community? These are areas that can be improved upon with the suggested language updates we discussed above in action step two.

Are there symbols or graphics that will welcome GSM, such as safe space signs, flags depicting an upside-down rainbow triangle, or “all-gender” verbiage in lieu of gender-specific? Both would make easy additions that signal to patients they are in an inclusive space. However, it is important to distinguish the difference between saying a space is safe, and actually making a space safe. A space can only be safe if the entire team of providers and office staff are on board. Labelling a space as safe when it is not has the propensity to cause further harm. Be sure before these indicators are put up in your practice, everyone is ready to support such efforts.

6. Be prepared to mess up—but don’t let that deter you from trying.

Any etymologist will tell you that languages are living things that are constantly evolving. Developments such as these can make it challenging to stay current on which terminology is most beneficial to our growing society. Sometimes just the fear of making a mistake can be intimidating enough to discourage people from trying. What is most important is not how well you use updated language but that you are trying. Your effort matters, and it is what will move the needle in the right direction. Cultural responsiveness is not knowing every nuanced detail of every demographic group. Cultural responsiveness is being willing to reflect and modify your viewpoints when presented with information that differs from what you previously held to be true. Try to accept that just with learning any new skill, mistakes are bound to happen. When they do be prepared to learn, and then move forward with that new knowledge in mind.

To learn more about how you can work to establish and maintain a practice of allyship and inclusivity, check out this course on cultural humility by MedBridge instructors Leah B. Helou, PhD, CCC-SLP, and Wynde Vastine, MA, CCC-SLP.

- Cusick Director, J., Seeberger Director, C., Woodcome, T., Oduyeru Manager, L., Gordon Director, P., Shepherd, M., Parshall, J., Santos, T., Medina, C., Gruberg, S., Mahowald, L., Bleiweis, R., Graves-Fitzsimmons, G., & Zhavoronkova, M. (2021, November 7). The State of the LGBTQ Community in 2020. Center for American Progress. Retrieved November 23, 2021, from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/state-lgbtq-community-2020/.

- Ellis, S. K. (2019). GLAAD Accelerating Acceptance 2019 Executive Summary. GLAAD.

- Jones, J. M. (2021, November 20). LGBT identification rises to 5.6% in latest U.S. estimate. Gallup.com. Retrieved November 23, 2021, from https://news.gallup.com/poll/329708/lgbt-identification-rises-latest-estimate.aspx.

- Russell, S. T., Pollitt, A. M., Li, G., & Grossman, A. H. (2018). Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(4), 503–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.02.003

- Schmidt, S. (2021, February 26). 1 in 6 Gen Z adults are LGBT. and this number could continue to grow. The Washington Post. Retrieved November 23, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2021/02/24/gen-z-lgbt/.

- Who Are We? Consortium. (n.d.). Retrieved November 23, 2021, from https://www.consortium.lgbt/intersex-inclusive-flag/.