Bridging the Gap: Integrative Medicine in Modern Clinical Practice

July 29, 2024

9 min. read

As a health professional, do you incorporate integrative approaches into your clinical practice? A recent report from Harvard Health indicates that about two-thirds of Americans aged 50 to 80 now use some form of integrative medicine for their health and well-being.1

Integrative medicine first emerged in the U.S. in the 1930s through the efforts of medical practitioners called "drugless healers." These practitioners, including naturopaths, chiropractors, midwives, herbalists, shamans, indigenous medicine practitioners, and others, were marginalized after the 1910 Flexner Report, which called for the standardization of medical education and led to the exclusion of many alternative practices.2

In this article, we will explore the historical origins, modern definitions, clinical uses, community support, guiding principles, and challenges and opportunities of integrative medicine.

Origins and Evolution of Integrative Medicine

The term "drugless healers" is historically associated with a 19th-century Germanic philosophy centered around a "nature cure" that embraced the body's inherent drive to maintain health. This drive was regarded as an intelligent "vital force," considered divine by some, permeating every atom, molecule, and cell. The philosophy emphasized natural remedies and holistic approaches, contrasting sharply with the emerging pharmaceutical and surgical practices of the time. This vital force was seen as capable of re-establishing homeostatic conditions to promote healing.3

Fast forward to the present, the Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine defines integrative medicine (IM) as "healing-oriented medicine that takes account of the whole person, including all aspects of lifestyle. It emphasizes the therapeutic relationship between practitioner and patient, is informed by evidence, and makes use of all appropriate therapies."4

To further elaborate on this modern approach, the Center outlines eight defining principles. These principles include openness to new paradigms founded in good science and the prioritization of illness prevention and health promotion. Uniquely and critically, the last principle states, "Practitioners of integrative medicine should exemplify its principles and commit themselves to self-exploration and self-development."

Integrative Medicine in Clinical Practice

As a health professional who has incorporated integrative medicine into my practice, I was inspired to do so through self-exploration and engaging in contemplative practices. These practices can take many forms, both ancient and modern, and often involve mindful movement followed by being still, which helps calm the mind.

Regularly practicing these activities can draw our attention to our inner experiences. Some people even describe becoming more aware of their internal sensations or vital energy, while others experience spontaneous insights, inspirations, or a boost in creativity.

The integration of these practices into clinical settings can be highly beneficial:

Incorporating acupuncture and mindfulness practices for pain management.

Utilizing yoga therapy to support all aspects of a biopsychosocial-spiritual approach to self-care for individuals with chronic conditions.

Employing contemplative practices featuring mindful movement to assist with nervous system self-regulation to reduce stress and enhance patient outcomes.

Evidence-based research supports these approaches, showing significant benefits in various health conditions. For instance, acupuncture can effectively reduce chronic pain, yoga therapy can alleviate symptoms of depression and anxiety, and mindfulness meditation can enhance mental health and reduce stress.

Building Community and Professional Support

Community and professional support are crucial for promoting and sustaining integrative medicine practices. Engaging in community activities and professional networks can provide the encouragement and resources necessary to embrace a more integrative form of healthcare.

Medbridge has supported several courses that feature integrative approaches to rehabilitation. These courses have been instrumental in providing training and resources for health professionals looking to incorporate integrative practices into their work. Additionally, networking with colleagues on a similar path is invaluable for professional growth and development.

For instance, conferences offered by the International Association of Yoga Therapists bring together health professionals from various disciplines to discuss and share insights on integrative practices. The science supporting mindfulness, meditation, and yoga for autonomic nervous system regulation has been creating significant connections with Western medicine.

The American Holistic Health Association and the Academy of Integrative Health & Medicine have also played key roles in promoting integrative practices through professional development, research, and advocacy. These organizations offer resources, training, and platforms for practitioners to share experiences and learn from each other.

Guiding Principles for Integrative Physical Therapy

Integrative medicine can significantly impact the field of physical therapy, providing a more holistic approach to patient care. A key publication that has contributed to the field is the Guiding Principles for the Practice of Integrative Physical Therapy, co-authored by a team of experts in the Physical Therapy Journal (PTJ), including myself.5

Lead author, Catherine Justice, envisioned starting a conversation within the APTA to explore whether integrative physical therapy would become yet another facet of specialization or possibly shape how future professionals are educated. Such a conversation seems timely, given that physical rehabilitation and surgery remain some of the last disciplines to embrace an integrative medicine perspective.6

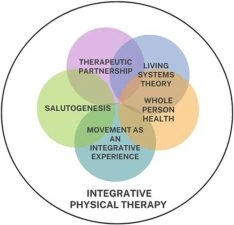

This open-access PTJ article outlines five guiding principles that form the foundation for integrating physical therapy into broader healthcare practices. Here are the key principles:

[caption id="attachment_17139" align="aligncenter" width="292"] Image copyright Catherine Justice, used with permission.[/caption]

Therapeutic Partnership: Focuses on building a collaborative and trust-based relationship between the patient and practitioner, emphasizing mutual respect and shared decision-making.

Living Systems Theory: Integrates the understanding that the human body is a complex, dynamic system. It encourages treatment approaches that recognize and work with this complexity to support overall health.

Whole Person Health: Emphasizes the importance of addressing the physical, emotional, and social aspects of a patient's health. It promotes a comprehensive approach to treatment that goes beyond symptom management.

Movement as an Integrative Experience: Recognizes the therapeutic potential of movement and encourages incorporating various movement-based therapies to enhance physical and mental well-being.

Salutogenesis: Focuses on factors that support human health and well-being, rather than on factors that cause disease. It promotes a positive approach to health by identifying and enhancing factors that contribute to a person's overall wellness.

Reflecting on how little the innate human capacity for healing is emphasized in today's medical practice, it is vital to consider the unique individuality and environment of each patient in their plan of care. Enhancing interprofessional communication and positioning the patient at the center of the care circle are essential steps toward more holistic and effective healthcare.

Overcoming Challenges and Embracing Opportunities in Integrative Medicine

Long-term opioid treatment in allopathic medicine remains prevalent despite its problems. Non-pharmacologic options for persistent pain, as recommended in guidelines such as the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, remain limited. A growing tide of interventional pain medicine, spine surgery, and joint replacement is simply not economically sustainable.6

Integrative medicine offers promising alternatives to traditional practices. For example, acupuncture, yoga, and mindfulness practices have shown efficacy in managing chronic pain and reducing reliance on opioids. By incorporating these methods, healthcare systems can provide more sustainable and holistic care options.

Incorporating these integrative practices is particularly relevant in places like Arizona, where a significant portion of the population is older adults with chronic pain and chronic illness. According to the CDC, between 2019 and 2021, chronic pain was present in 21 percent of the U.S. population.7 This is rapidly approaching rates of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

Given the rising rates of chronic pain and the associated economic burden, adopting integrative practices such as acupuncture, yoga, and mindfulness can help address these issues more effectively and provide patients with sustainable, holistic care options.

An Integrative Path Forward

Integrative medicine offers a holistic approach that considers the whole person, including lifestyle, therapeutic relationships, and evidence-based therapies. It emphasizes self-exploration and development for practitioners, creating a more inclusive and effective healthcare practice. By embracing these principles and fostering community support, we can bridge the gap between traditional and integrative practices, ultimately enhancing patient care and outcomes.

To learn more about how to incorporate integrative medicine into your practice, watch my Medbridge courses:

Aging Gracefully: Informed Choices for Health, Wellness, and Well-Being

Integrative Treatment For Patients Experiencing Chronic Pain

Self-Care Practices Inspired by Contemplative Neuroscience and Yoga

References

Harvard Health. US adults like integrative medicine but few discuss it with their doctors. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/us-adults-like-integrative-medicine-but-few-discuss-it-with-their-doctors

Cody, G.W. (2018). The Origins of Integrative Medicine-The First True Integrators: The Philosophy of Early Practitioners. Integr Med (Encinitas), 17(2), 16-18. PMID: 30962781; PMCID: PMC6396756. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6396756/

Cody GW. The Origins of Integrative Medicine-The First True Integrators: The Philosophy of Early Practitioners. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2018 Apr;17(2):16-18. PMID: 30962781; PMCID: PMC6396756.

Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine. Definition of Integrative Medicine. https://awcim.arizona.edu/health_hub/awcimagazine/what_is_integrative_medicine.html

Catherine Justice, Marlysa B Sullivan, Cheryl B Van Demark, Carol M Davis, Matt Erb. Guiding Principles for the Practice of Integrative Physical Therapy. Physical Therapy, Volume 103, Issue 12, December 2023, pzad138. https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/103/12/pzad138/7304129?login=false

Phutrakool, P., Pongpirul, K. Acceptance and use of complementary and alternative medicine among medical specialists: a 15-year systematic review and data synthesis. Syst Rev 11, 10 (2022). https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-021-01882-4

CDC. Chronic Pain and High-impact Chronic Pain Among Adults United States, 20192021. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7215a1.htm